This summer, Boris and I once again visited Vienna and met with our longtime friend — artist and President of the Bukharian Jewish Community of Vienna, Shlomo Ustoniiazov. We have been connected for many years through friendship, shared cultural and charitable projects, and our involvement in community life.

This meeting took place in a special setting — Shlomo’s studio. Surrounded by the scent of paint, the sight of canvases, and the soft light filtering through large windows, his works — filled with spiritual power and depth — are born. It was there, in this atmosphere of trust and reflection, that our conversation unfolded about his life, his art, and the paintings featured in this publication.

— Shlomo, what does your studio mean to you?

— For an artist, the studio is a sacred space where ideas are born, where creative thoughts finally find their way onto canvas or paper after long contemplation. It’s more than just a room — it’s my personal world, filled with a special creative atmosphere. It smells of paint and solvents; there’s silence and bright daylight. All of this becomes a hearth of inspiration — and sometimes of despair — in the search for the right artistic expression. In this solitude, I hold a dialogue with myself and my art. For me, it is a place of freedom and creation.

— When did you realize that painting was your path?

— I came to painting quite early. In my youth, I graduated from the Dushanbe Art School, then studied Russian philology at university. Art was always a part of my life; I drew whenever I could — though time was never enough. For many years, painting remained more of an inner need than a professional pursuit. I couldn’t afford to dedicate myself solely to art — I had a family to support. But art never left me. Only after retiring could I fully devote myself to it. Today, I feel that maturity brings the freedom and awareness from which my works are born.

— Among your paintings is one depicting four rabbis. What does it symbolize?

— In this painting, four great rabbis sit together at a table, deeply immersed in studying the holy books. On the table are fruits, wine, a Kiddush cup, books, candlesticks, and scrolls — all symbols of a tradition where the material and the spiritual are intertwined. The abundance on the table highlights the joy of their meeting.

The painting was commissioned by a young and successful businessman, Benyamin Motaev, who said he wanted to “seat at one table the leaders of different Jewish traditions” — to show that, ultimately, we are one people.

This work became a hymn to Jewish unity. Even when people differ in their beliefs, the Torah unites, brings peace, preserves tradition, and connects generations. On the canvas, there is an inscription from the Talmud: “The sages increase peace in the world.”

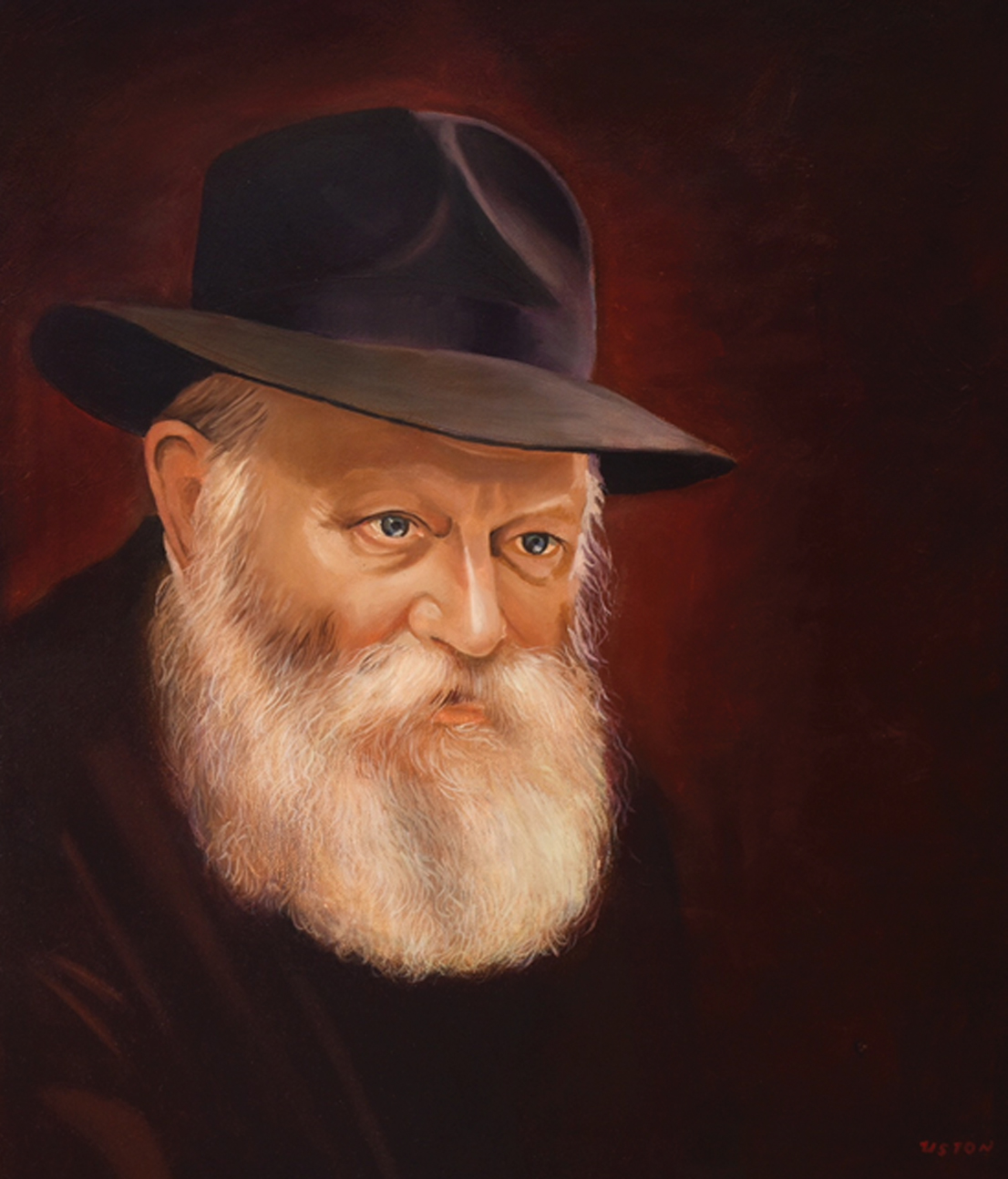

— Your portrait of the Lubavitcher Rebbe made a deep impression. How did you approach creating it?

— It is not merely a visual representation, but an attempt to touch the spiritual depth of a man who left a tremendous mark on generations. I wanted to capture not only the Rebbe’s appearance, but also his inner light — the soft yet piercing strength of his gaze. Through this work, I sought to express both a religious symbol and a universal image of spiritual inspiration — that point where art and faith merge into a single language.

— Some of your portraits are deeply personal, such as the one painted in memory of a departed elder…

— Yes. That portrait was created in memory of a man who left behind a kind and luminous name, a lasting impression in the hearts of family, friends, and many others. I wanted to convey his inner peace, dignity, and kindness, which were reflected in his eyes.

At the top of the canvas, at the request of his grandson, I inscribed the verse from Ecclesiastes: “A good name is better than fine oil…”

It serves as a reminder that a person’s true worth lives on in their deeds and in the memory of others. This portrait is not only an image, but also a gesture of gratitude and respect — to a man whose goodness continues to shine like a candle.

— You showed us the graphic work “The Captives,” to which you also wrote a poem. Why combine drawing and poetry?

— I wanted to merge image and word, so that they would enhance one another. The ink drawing depicts female figures imprisoned in towers, surrounded by snakes. The accompanying poem gives voice to this scene — the snake speaks, but another voice rises in response: a voice of protection, affirming the dignity of woman.

For me, this work is a reflection on the feminine essence — her beauty, strength, and creative power. I wanted it to become a hymn to woman as the Creator’s finest creation.

The world, kneeling before woman,

Blesses the Creator’s greatest design.

In her lies the essence and renewal of all creation,

From the beginning to the end of time.

— And finally, your still life. What message does it convey?

— The still life invites the viewer to pause and see ordinary things anew. In the classical tradition, a still life is not merely a depiction of objects, but a story about life itself — a fleeting moment suspended in time. It’s a hymn to abundance, joy, and the transience of life.

I chose simple, familiar objects: fruits, a glass of wine, vessels of metal and fabric. The fruits symbolize nature’s generosity; the pomegranate — the fullness of life; wine — the joy of the moment; and the cold gleam of metal — the fleeting nature of time.

I wanted the viewer to sense not only the objects themselves, but also the overall atmosphere — the feeling of a quiet celebration hidden within everyday life.

If, upon seeing this painting, someone takes a deeper breath and notices the beauty around them, then the work has fulfilled its purpose — and the artist can say: “Look — life is beautiful, right now.”

— Thank you for this conversation. We leave with not only the images of your paintings but also with the feeling of peace and depth born in your studio.

Interview by Boris Kandkhorov and Dr. Zoya Maksumova